Pricing is one of the most difficult issues for new businesses, but it is also one of the most critical. While there are some general principles that should be applied by all businesses, there is no one size fits all model for setting prices.

Creating the right image through pricing

Pricing affects profit, but it also plays a major role in forming your brand’s image. Set your prices too high and you will be perceived as not offering good value for money, set prices too low and you may be perceived as cheap. The basic starting point for setting prices is an understanding of costs – you cannot sell your goods or services for less than the cost of production, at least not for very long.

Costs of production include the direct costs of each item of product or hour of service – such as raw materials and wages – but they also include longer term and indirect costs, such as rent and electricity. An element of profit should also be included as a cost when considering price. No one wants to be in business to just break even.

Looking at costs will give you a floor price below which you should not sell. It is better to do no business at all than to have a loss-making business. Up to this point in the process, pricing is a science dependent on good and accurate information about costs; the next steps are an art requiring judgement about how the market will react to your pricing decisions.

The context for your pricing

The next step for most businesses is to look at the competition and see what they are charging. Most small and new businesses see themselves as price takers. That is, they must charge what the market dictates. This may be true in some cases, but most small or new businesses should be able to use their greater flexibility to position themselves to charge a premium price.

This will depend on the product or service being sold. Every buyer wants the cheapest price when it comes to buying a commodity item (something that is the same no matter where you buy it), but not every item is a commodity.

Everyone wants the cheapest sofa, but no one wants to get their hair done by the cheapest hairdresser in town. How do you know which hairdresser is best? Well, it is probably not the cheapest. The price a supplier charges sends out a strong signal about the quality of the goods or services supplied. There are many areas where buyers want the best they can afford – no one wants the second-best lawyer, for example. And even looking at sofas, people want quality at a price, not just the cheapest on the market.

Charging an adequate price

Charging an adequate price also allows a supplier to pay for a good after-sales or support service, thus reinforcing the quality perception. Where a sale is made at a break-even cost, there is no room to deal with any customer queries that may arise after the sale. The idea that price sends a signal about the quality of the goods or services being offered should be included in every business’s approach to price setting. No business wants to be perceived as expensive, but being seen as cheap is also damaging.

Each business must balance the too-expensive v too-cheap seesaw for themselves, but it helps to understand the needs of your own business. In approaching the issue of price, a business needs to understand its own limiting constraints. It is all very well to charge as low a price as possible if you can increase your output almost infinitely at little or no cost, such as may be possible with a software product or if you have a large number of air plane seats to fill.

Many businesses, however, have staffing, premises or other constraints to resolve before they can increase production; for businesses in this position, increased pricing may allow them to grow profits working within existing constraints.

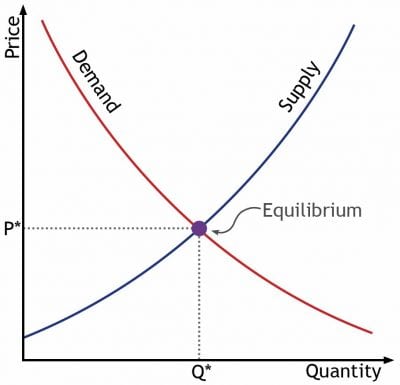

As a last idea to consider we have the supply versus demand curve beloved of economists. On the left hand side – where the price is low – there are lots of buyers, but nobody wants to sell. On the right hand side – where the price is high – everybody wants to sell, but there are not many buyers. In the theory, the equilibrium point at the middle is where buyers and sellers meet.

For a small or new business, this diagram shows something else: that there are a small number of buyers who are willing to pay a premium price. There can be profit in addressing these buyers, offering them a reason why they should buy from you rather than at the market price. This may be a better service, branded product or simply a higher price.

Key considerations for pricing

- Costs set a floor for pricing

- Pricing sends a message

- Know your own business constraints

- There are premium buyers out there

To illustrate these ideas more fully, I thought it would be helpful to share a case study. The names are changed and some of the details reflect experience with more than one business, but the case study does fairly reflect actual events.

Case study: setting pricing for a quality systems company

The problem

Jason had a quality systems design implementation and training business. Jason himself is highly qualified and very experienced in designing and implementing quality systems within a specialised area. His business employed himself and three other people: Jason as a consultant, two associates and an admin person.

Jason would hold an initial meeting with clients and design a solution to meet their requirements. One of his associates would then implement Jason’s design.

Jason was working 70+ hours per week and feeling overwhelmed when he came to me. The obvious first question was: why not hire more staff? Jason felt that what he needed was another consultant at his level, but that the cost would be considerable and the extra income would not be all that much, as a new employee could not be expected to do the 70 hour weeks that Jason was doing.

While expanding the staff was considered as desirable in the medium term, some change was needed in the short term. We looked at the company’s income. Jason was charging 50 hours per week to clients and his two associates were charging nearly 40 hours each. Clearly, there was a limiting constraint in terms of available hours.

The analysis

I suggested that a fresh look at pricing was needed. The business was profitable, though not as profitable as it should have been. Due to the long hours worked at the operations end of the business, very little attention was being paid to cost control. Any issue that arose was solved by throwing money at it.

We looked at the other suppliers that Jason was in competition with. The market involved one major company with about 25% of the market and a number of smaller businesses similar to Jason’s, none with more than 5% market share. Their pricing was opaque, none had a published set of daily rates as they all priced each job individually.

We then looked at Jason’s customers. They were all strong businesses in an expansion phase looking to beef-up their quality controls. I suggested to Jason that they were all potentially premium customers, willing to pay a good price if they were convinced that Jason could deliver a better service than his competitors.

The solution

As a result of this review, Jason increased his rates by 50%. While this certainly increased profits, Jason considered that that was not the most important benefit. The additional revenue allowed him to hire a second consultant and a third associate. He is now working 50 hours, rather than 70 hours, per week himself and devoting his energies to developing the business – with a lot less time taken up in firefighting.

Although Jason did loose some customers, he has a much better relationship with the customers he retained and he has seen no slowdown in new enquires or new business. The increased level of service that Jason can provide to his customers allows him to pitch his company as the best in the business, effectively being seen as the premium supplier with the major company seen as the bulk supplier.

About the author

Patrick O Flaherty

Patrick O Flaherty

Patrick is a business consultant and Enterprise Ireland mentor. His expertise spans areas such as financing and funding, as well as business development and internal structures and processes – with a particular focus on projections, business plans, costings and pricing.

Recent articles

Raise Your Startup’s Visibility & Credibility By Entering These Competitions

Founder Perspectives: Lessons From Building Businesses In Sustainability

Tech Startups In The Age Of AI: Alumnus Paul Savage On Speed, Quality & Risk

Fourteen Startup Founders Graduate From Phase 2 Of New Frontiers In Tallaght

Eleven Founders Graduate From New Frontiers In The Border Mid-East Region

Laying The Right Groundwork Helps Startups Prepare For Export Success

Startup In Dublin: Learn More About New Frontiers On TU Dublin’s Grangegorman Campus

Patrick O Flaherty

Patrick O Flaherty